In Awards, Impact Wins

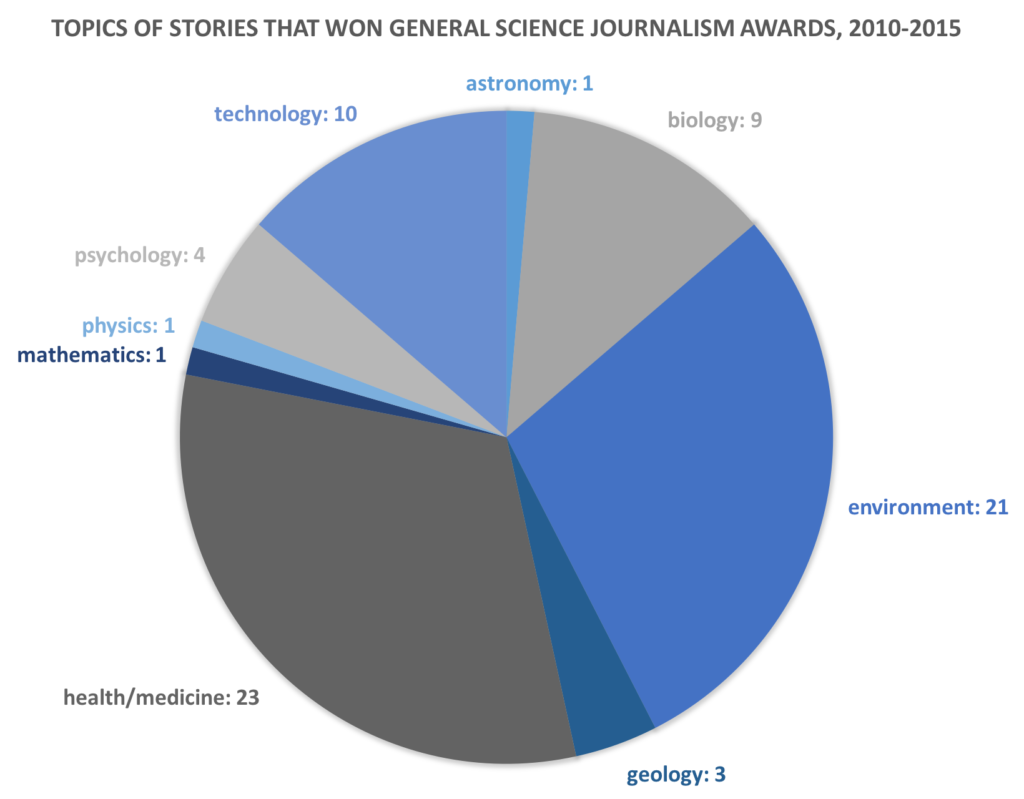

If you think you’ve noticed an imbalance in the topics covered by award-winning science stories lately, you’re right. However wide the umbrella of science journalism, environment and health stories tend to win general science journalism awards, leaving basic science and mathematics in the dust.

Basic-science topics get less coverage overall, but does that explain the lopsided awards count? It’s more likely that a physics or math story falls short on something awards competitions look for: an obvious impact on society.

One of the first steps in launching Showcase was to build a database of recent award winners. To start, I collected six years of stories that had won the AAAS Kavli awards, the National Academies’ Keck awards, CASW’s own Evert Clark/Seth Payne awards and NASW’s Science in Society awards. Our goal was to find winning stories that covered the breadth of science journalism. We want Showcase to thrive with diversity, showing how writers overcome different obstacles to create the best possible story.

But the results surprised me. Despite the fact that we had selected general science journalism awards, there was not much diversity in subject matter among the winners. Health and environment stories won time and time again. I was shocked (and to be perfectly honest, a little saddened) to see that over the last six years only one award had gone to a physics story. The same is true for astronomy and mathematics. Chemistry doesn’t even show up.

A smaller universe

Now, you can argue that this isn’t a bias in the awards at all, but a bias in science journalism. A quick glance at science stories today shows that physics and mathematics stories are much rarer than health and environment stories. Some science journalists have even gone so far as to say that physics is the worst field to write about (see this excellent rebuttal by Jennifer Ouellette). “It’s a smaller universe, you might say, of people who are interested in reading and writing about astronomy—and physics even more so,” says Paul Raeburn, a science journalist who has covered nearly every science beat and regularly analyzes the media in a blog at UnDark.

In turn, fewer physics and mathematics stories are submitted for awards, says John Carey, who has organized the judging for the Clark/Payne award for young science journalists for more than two decades.

Still, I felt there was a deeper story behind these numbers. So I set out to determine why so few basic science stories have received prestigious awards—awards I’m sure they deserve.

Only connect?

The answer doesn’t fall under the guidelines for these awards, which are quite general. AAAS describes the Kavli awards, for example, as “an internationally recognized measure of excellence in science journalism.”

It’s left to judges to determine what goes into excellence. For CASW President Alan Boyle, who has covered astronomy and science for 19 years and is often asked to judge stories for various awards, that list includes telling a story that is accurate (which is made all the more difficult by the inherent complexity of the hard sciences), engaging, novel and—above all else—makes an impact.

Award-winning stories should touch people. “When you write a story about cancer or heart disease, you don’t have to tell people why they should read it,” says Raeburn. But when it comes to astronomy and physics stories, it’s up to the reporter to connect the reader to the story. “If you’re devoting a lot of time to a subject, you really have to think about and spell out in the report what this means, what’s the big picture?” says Boyle. “It doesn’t have to be a cure for cancer, it doesn’t have to be a better iPhone, but you do have to address that question.”

Boyle points to the recent discovery of gravitational waves, ripples in the fabric of spacetime that Einstein predicted a century ago but were unverified until this year. “It’s arguably one of the greatest scientific findings of the past century, but in terms of how that resonates with society at large, it’s kind of a geeky topic,” he says. “Is it going to make for a better iPhone? No, but it does change the way that people look at the universe. And perhaps the way that prizes are awarded doesn’t fully reflect that.”

Explaining a story’s impact is crucial and in some ways obvious. Any student in a Journalism 101 class will tell you impact should be in every pitch they write. And yet writers often fail to mention how a new physical discovery will change a reader’s world. Carl Sagan-like discussions of cosmic implications fall prey to tight deadlines and word counts.

Boyle admits that a lot of his own stories don’t take the time to fully explain what a scientific discovery means to the general public. It’s easy to get so swept up in the coolness of the discovery or bogged down by the details that you forget to take a step back and describe how the news is really going to change our perception of the universe, he says.

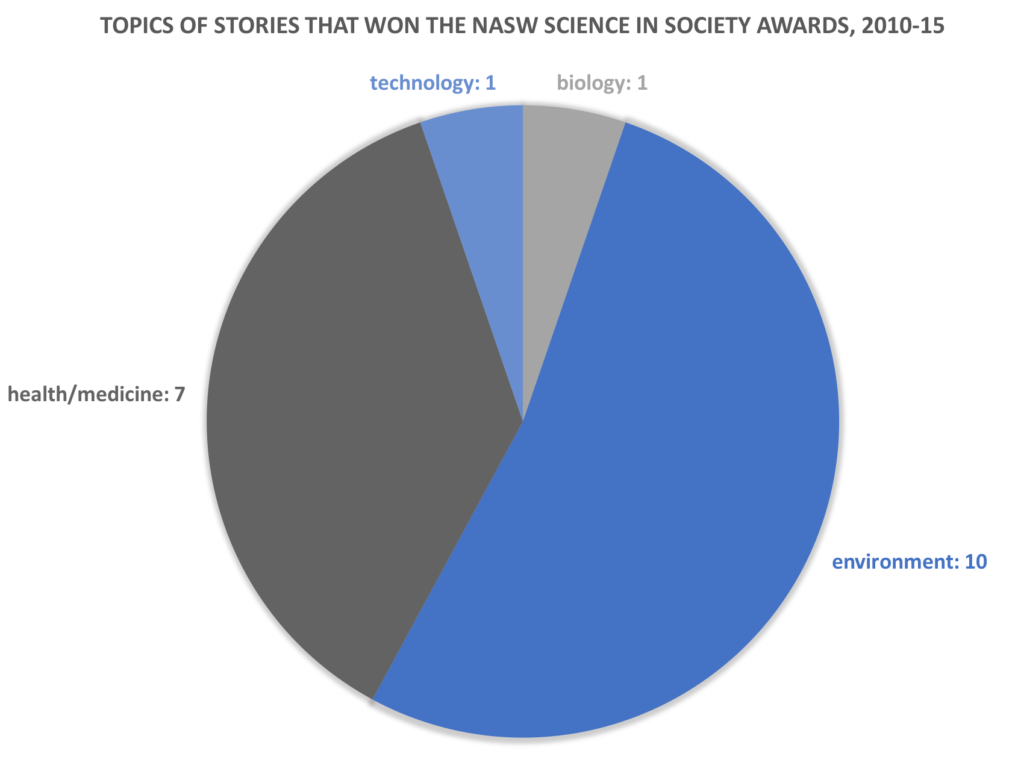

It’s not surprising that the NASW Science in Society awards over the last five years have been given to a high number of environment and health stories. The NASW awards specifically look for impact. They’re designed to “honor and encourage outstanding investigative and interpretive reporting about the sciences and their impact for good and ill.” Here the biology and technology beats make up the the loneliest stories on the block, and the mathematics and physics beats don’t even live in the same neighborhood.

And yet the Kavli, Keck and Clark/Payne awards—with their high percentage of environment and health stories—appear nearly as biased toward social impact as the awards that are explicitly designed to recognize such stories.

The solution? Submit! (but don’t forget about impact)

I can imagine that many journalists might look at past winners to determine which stories they should submit themselves. Could there be a self-reinforcing cycle where writers submit stories similar to those that have won in the past? Carey doesn’t think so, but Boyle speculates that it might be a possibility. “It may be that people don’t enter those competitions because they don’t think that they’re in the sweet spot for that competition,” Boyle sayes. “But maybe they’re right there, and they still should enter.”

No matter the reason, both Carey and Boyle encourage journalists to enter more physics and mathematics stories into award competitions.

It’s true that physics and mathematics writers have their work cut out for them. But when the reporting has paid off and it all comes together—from the nitty-gritty details of a discovery to its sweeping impact on society—the final product is beautiful.

Take Dennis Overbye’s New York Times story on the search for the Higgs boson. Analogies, quirky yet lovable characters and statements explaining why the reader should care about this quest effortlessly sweep in and out of the story to paint a picture of an underappreciated particle that could explain how everything fits together in “the jigsaw puzzle of reality.” It’s no wonder this story won a Keck award in 2014.

Overbye’s award is a testament to the power of a well-written physics story and a reminder that stories that connect the reader to basic science—challenging as they might be to report and write—are worth the effort. Even if an award isn’t the immediate goal, continually striving toward a story that is award-worthy can only make the story better.

| Shannon Hall is CASW Showcase’s project manager and an award-winning freelance science journalist based in Colorado. Follow her on twitter @ShannonWHall. |