Is There a Gender Bias in Science Writing Awards?

Science news desks and pressrooms are no longer boys’ clubs. We women science reporters infiltrate graduate programs (my 2015 graduating class in NYU’s Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program included 11 women and 0 men) and overwhelm conferences. In the 2018 National Association of Science Writers (NASW) membership survey, 64 percent identified as female.

But even as the ranks of female reporters have grown, male names still tend to dominate science bylines. That much was revealed in 2016 when a team of volunteers conducted the first-ever examination of gender disparities in bylines, called the Science Byline Counting Project.

A Pipeline Problem? |

| In 2017, The Open Notebook conducted a survey to determine whether the gender disparity in bylines could be explained by a “pipeline problem.” Perhaps women science journalists do not pitch as many features and therefore do not receive as many bylines. But the survey revealed no gender differences in pitching habits. |

The project revealed that while women and men wrote an equal number of short science news stories (and occasionally women wrote more), men wrote more features. At Scientific American, during 2015, 81.2 percent of the features were written by men. At Wired, 73.6 percent were written by men. It’s an important dichotomy to note, given that features give writers the opportunity to showcase their writing style and establish credentials that could lead to further career opportunities. They are also much more likely than news stories to win awards.

So perhaps it’s no surprise that previous work found that men were more often published in popular anthologies. During the “XX Question” session at ScienceWriters2013, journalist Deborah Blum, then teaching at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, presented a number of slides revealing gender imbalances within science journalism. That research (which was presented in more detail the next year at a conference and was the inspiration behind the byline project) showed that women wrote a mere 20 percent of the stories published in Best American Science and Nature Writing from 2009 to 2013 (a balance that has shifted in recent years).

Despite the imbalance in anthologies, Blum’s team also reported that the NASW Science in Society awards honored women 58 percent of the time over that same period, while the AAAS Kavli Science Journalism writing awards did so 48 percent of the time.

What About Today?

More than five years have passed since Blum displayed her counts to a packed room at ScienceWriters2013. During that time, Showcase has begun tracking science-writing awards — giving us the perfect platform to analyze the winners’ list with more recent data.

It’s sometimes said, for example, that men are more likely than women to win prestigious awards in science writing. So we decided to take a look at the evidence supporting that statement by tallying the last 10 years’ worth of winners of the eight major science journalism awards we consider for Showcase.

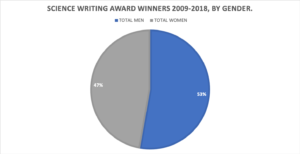

We found no clear gender bias — at least not overall. Instead, women received 47 percent of the awards while men received 53 percent.

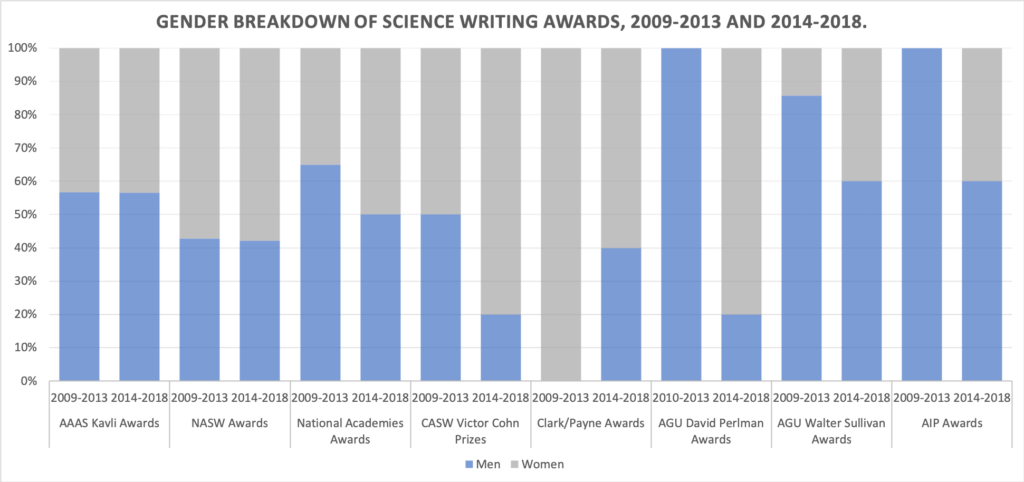

When you look at individual awards, on the other hand, it’s easy to find differences in gender balance. In what follows, note that these are small numbers without statistical power.

The AAAS Kavli Science Journalism awards, for example, bestowed 57 percent of their awards on men during the 10-year period, whereas 57 percent of NASW Science in Society journalism awards were presented to women. In other words, those ratios have barely changed in the five years since the byline project.

The American Geophysical Union’s David Perlman and Walter Sullivan awards as well as the American Institute of Physics Science Communication Awards tend to go to male writers overall — not surprising given that the awards focus on the heavily male-dominated fields of geology and physics. AIP’s pool of winners was particularly lopsided, with men winning 75 percent of the time. AGU’s Perlman Award was in the same boat until 2015; since then, the Perlman winners have all been women. Nanci Bompey, who oversees the AGU journalism awards, notes that in recent years there have been attempts to get more applicants for the Perlman award overall. Since 2016, when she joined the team, there have been equal numbers of male and female candidates.

A contrasting picture can be seen in the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award for young science journalists, now awarded by CASW, and CASW’s Victor Cohn Prize for Excellence in Medical Science Reporting, which have tended to go to women. From 2009 to 2016, every Clark/Payne award went to a woman. These counts may reflect the higher prominence of women in medical writing and the predominance of women among early-career science writers, says CASW Executive Director Rosalind Reid. The byline counting project found that women dominated magazine health and medicine bylines.

Overall, the split between men and women in the winners’ lists is fairly even. That said, it does not reflect the high numbers of women now active in science journalism.

Finally, these counts have important limitations. In particular, we don’t know the relative numbers of men and women who submit their stories for awards, so there’s no reason to infer bias in the awards process. Our data don’t represent the full range of awards, nor the total awards given by each program (we only looked at awards for written stories — skipping other media and special categories). And while we looked at a decade’s worth of data, the small numbers mean these counts should not be over-interpreted. (That’s particularly true with AIP, which did not grant an award for newspaper, magazine and online stories in 2010 or 2012, leaving us with just eight total awards to count.)

It should also be noted that while counting women winners has become a recent obsession, some believe that tallies won’t bring real social progress. In an Op-Ed published in The New York Times on the day the Academy Awards were presented, Katherine Manu-Ward, the editor in chief of Reason magazine, argued that quotas and tallies divert attention from the need for upstream social change. “The real work of recalibrating representation,” she said, “must be done privately and incrementally, one day at a time.”

| Shannon Hall is CASW Showcase’s project manager and an award-winning freelance science journalist based in Colorado. Follow her on twitter @ShannonWHall. |