The Stargazers

In this feature for Science magazine, freelance science journalist Joshua Sokol describes how Indigenous Maya are working with Western scholars to understand the ancient Maya astronomy buried by Spanish colonists hundreds of years ago. Sokol has won awards from CASW, the American Astronomical Society, the American Institute of Physics, and the American Geophysical Union.

ZUNIL, GUATEMALA—As the Sun climbs over a hillside ceremony, Ixquik Poz Salanic invokes a day in the sacred calendar: T’zi’, a day for seeking justice. Before she passes the microphone to the next speaker, she counts to 13 in K’iche’, an Indigenous Maya language with more than 1 million present-day speakers in Guatemala’s central highlands. A few dozen onlookers nod along, from grandmothers in traditional dresses to visiting schoolchildren shifting politely in their seats. Then the crowd joins a counterclockwise procession around a fire at the mouth of a cave, shuffle dancing to the beat of three men playing marimba while they toss offerings of candles, copal, and incense to the wind-licked flames.

Poz Salanic, a lawyer, serves as a daykeeper for her community, which means she keeps track of a 260-day cycle—20 days counted 13 times—that informs Maya ritual life. In April, archaeologists announced they had deciphered a 2300-year-old inscription bearing a date in this same calendar format, proving it was in use millennia ago by the historic Maya, who lived across southeastern Mexico and Central America. In small villages like this one, the Maya calendar kept ticking through conquest and centuries of persecution.

As recently as the 1990s, “Everything we did today would have been called witchcraft,” says fellow daykeeper Roberto Poz Pérez, Poz Salanic’s father, after the day count concludes and everyone has enjoyed a lunch of tamales.

The 260-day calendar is a still-spinning engine within what was once a much larger machine of Maya knowledge: a vast corpus of written, quantitative Indigenous science that broke down the natural world and human existence into interlocking, gearlike cycles of days. In its service, Maya astronomers described the movements of the Sun, Moon, and planets with world-leading precision, for example tracking the waxing and waning of the Moon to the half-minute.

In the 19th century, Western science belatedly began to comprehend the sophistication of Maya knowledge, recognizing that a table of dates in a rare, surviving Maya text tracked the movements of Venus in the 260-day calendar. That discovery—or rediscovery—set off a still-ongoing wave of research into Maya astronomy. Researchers scoured archaeological sites and sifted through Mayan script looking for references to the cosmos. Hugely popular, the field also spawned a fringe of New Age groups, doomsday cultists, and the racist insinuation that the Maya must have had help from alien visitors.

In the past few years, slowly converging lines of evidence have been restoring the clearest picture yet of the stargazing knowledge European colonizers fought so hard to scrub away. Lidar surveys have identified vast ceremonial complexes buried under jungle and dirt, many of which appear to be oriented to astronomical phenomena. Archaeologists have excavated what looks like an astronomers’ workshop and identified images that may depict individual astronomers. Some Western scholars also include today’s Maya as collaborators, not just anthropological informants. They seek insight into the worldview that drove Maya astronomy, to learn not only what the ancient stargazers did, but why.

And some present-day Maya hope the collaborations can help recover their heritage. In Zunil, members of the Poz Salanic family have begun to search for fragments of the old sky knowledge in surrounding communities. “It’s more than just wanting the information,” says Poz Salanic’s brother, Tepeu Poz Salanic, a graphic designer and also a daykeeper. “We say you’re waking up something that has been sleeping for a long time, and you have to do so with care.”

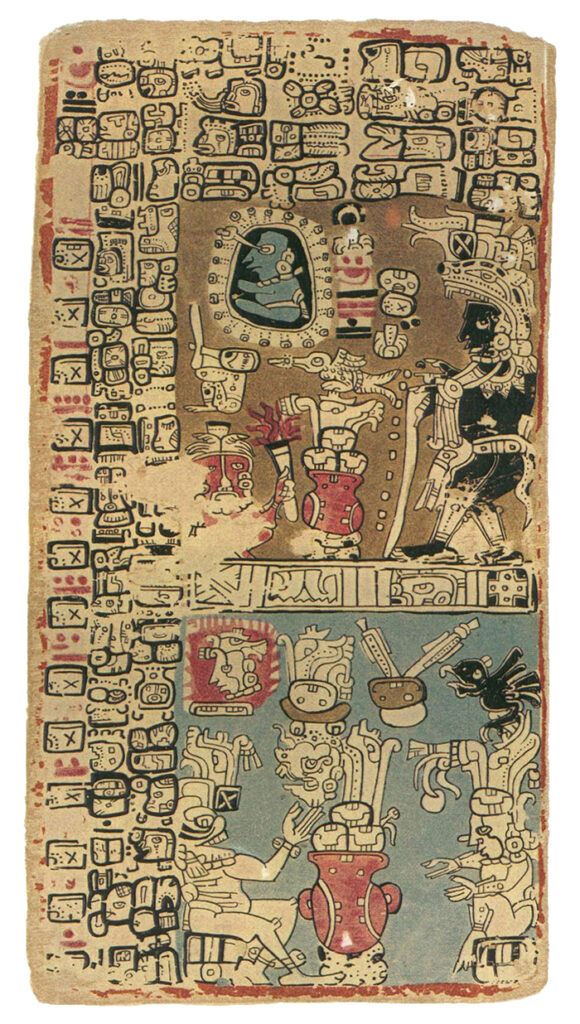

After the Spanish arrived in the 1500s, the conquerors set out to extirpate Maya knowledge and culture. Although the Spanish were aware of some of the intricacies of Maya culture, including the 260-day calendar, priests burned Maya texts, among them accordion-folded books of bark paper called codices, painted densely with illustrations and hieroglyphs. “We found a large number of books,” wrote a priest in Yucatán. “As they contained nothing in which there were not to be seen superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all, which they regretted to an amazing degree, and which caused them much affliction.” Only four looted precolonial volumes surfaced later, all in foreign cities with vague chains of custody.

By the end of the 19th century, one codex was in a library in Dresden, where it fell into the hands of a German librarian and hobbyist mathematician named Ernst Förstemann. He couldn’t puzzle out the hieroglyphs, but he deciphered numbers written in a table.

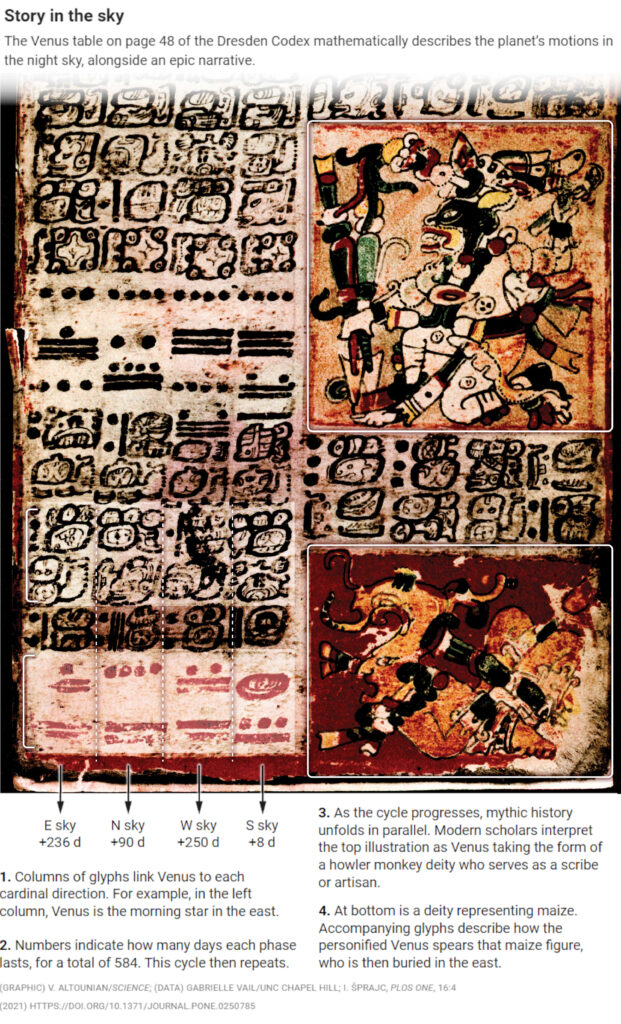

These were dates in the 260-day sacred cycle, Förstemann saw. And based on the intervals of time between the dates, the table had to be a guide to the motions of the planet Venus, which cycles through a 584-day, four-part dance in which it appears as the morning star, vanishes from the sky, reappears as the evening star, then vanishes once more.

Since then, researchers studying the codices and stone inscriptions at archaeological sites have recognized that precolonial Maya clocked motions of the Sun, Moon, and likely Mars with sophisticated algorithms; that they likely aligned buildings to point at particular sunrises; and that they inscribed celestial context such as the phase of the Moon into historical records.

Scholars have limited evidence of each practice, capturing narrow, through-a-keyhole glimpses of customs that evolved across a vast territory over thousands of years. But the archaeological evidence suggests that between 2000 or 3000 years ago, Maya communities embraced a set of mathematical concepts linked to celestial events and other repeating patterns that influenced personal rituals and public life, eventually growing into an intricate, interlocking system.

One early and overarching goal was to meter the flow of time. The first inscriptions of the 260-day cycle, for example, date to this early period. No one agrees on the precise significance of the sacred count: It could be the approximate interval between a missed period and childbirth, how long it takes maize to grow, or the product of 20, the fingers-plus-toes base of Maya math, and 13, another common Maya number that could itself be justified by the number of days between a first crescent Moon and full Moon.

Around this time, the early Maya also invented a yearlong solar calendar that would have been helpful for seasonal tasks such as planting corn. By 2000 years ago, they had begun to track a third calendar called the Long Count, a cumulative, ongoing record of days elapsed since the calendar’s putative zero date in 3114 B.C.E. This would have enabled Maya scribes to scan back through centuries of historical events on the ground and in the sky.

Archaeologists think all these ideas and their connections to celestial movements may be enshrined in the crumbled architecture of the Maya world. In one famous example from late-stage Maya history, at the site of Chichén Itzá in Mexico, a snake head sculpture sits at the foot of a staircase going up a massive pyramid. On every spring and fall equinox, when night and day are the same length—and huge throngs gather to watch—the Sun casts sharp, triangular shadows down the staircase, creating what looks like the diamondback pattern of a rattlesnake.

Then again, a similar shadow is cast for a few days before and after the equinox, too. Proponents can’t prove the 10th century builders meant to mark this particular day, nor can skeptics disprove it.

Given a starry sky’s worth of possible patterns, says Ivan Šprajc, an archaeologist at the Institute of Anthropological and Spatial Studies in Slovenia, “The reality is that for any alignment you can find some astronomical correlate.” But Maya scholars are now identifying cases in which statistical weight from many sites or other details lend extra credibility to the astronomical links.

Two hours downslope from Zunil, dappled light filters through the tree canopy at Tak’alik Ab’aj, the ruins of a proto-Maya city laid out in a neat grid along a trade route. There, a battered stone stela excavated in 1989 bears a Long Count date fragment that may refer to an unknown event around 300 B.C.E.

Christa Schieber de Lavarreda, the site’s archaeological director, points to a flat stone, considered an altar, found face-up just a few feet away, which archaeologists think was installed at the same time as the stela. Its surface is indented with delicate carvings of two bare feet, toe pads included, as if a person stood there and sank in a few centimeters. “Very ergonomic,” she jokes. If someone stood in those prints, she says, they would have faced where the Sun rose over the horizon on the winter solstice, the year’s shortest day.

For Zunil daykeepers and other Indigenous groups, sites like this are sacred places where ancient knowledge comes alive; their right to conduct ceremonies here is codified in Guatemalan law.

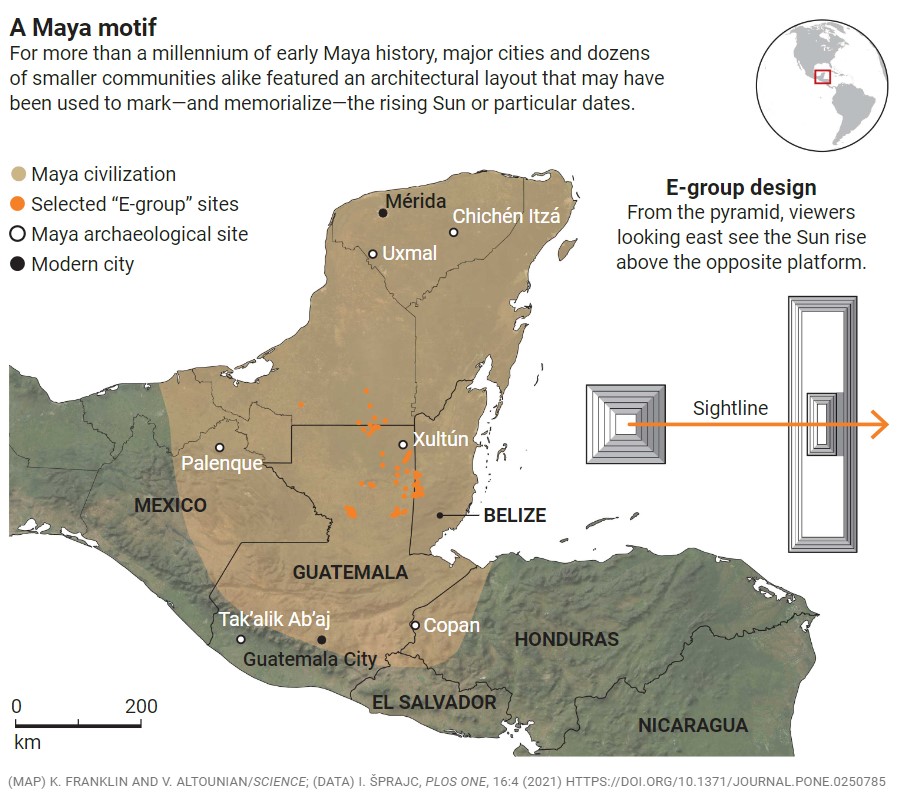

The surrounding ancient city contains more clues to ancient astronomical awareness. The plaza containing the date inscription, for example, belongs to a common style that Maya city planners apparently followed for more than 1000 years. The eastern side of the plaza features a low, horizontal platform running roughly north to south, with a higher structure in the middle. On the western side is a pyramid topped with a temple or the eroded nub of one (see graphic, below).

Beginning in the 1920s, archaeologists began to clamber up these pyramids in the early mornings and look east, toward the rising Sun over the platform, suspecting the complexes might mark particular solar positions.

A stream of recent data supports the idea, Šprajc says. In 2021, he analyzed 71 such plazas scattered through Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize, measured either with surveying equipment on his own jungle forays or with lidar, a laser technology sensitive to the faint footprints of ruins now buried under forest and earth. In the most widespread shared orientation, someone standing on the central pyramids would see the morning Sun crest over the middle structure of the opposite platform twice a year: 12 February and 30 October, with a suggestive 260 days in between. Perhaps, Šprajc argued in PLOS ONE, these specific sunrises could have been marked with public gatherings or acted as a kickoff for planting or harvesting festivals.

Ongoing research suggests designers of even older architecture shared a similar worldview. In 2020, archaeologist Takeshi Inomata of the University of Arizona used lidar data to spot a vast, elevated rectangular platform, with 20 subplatforms around its edges, that stretched 1.4 kilometers in Tabasco, Mexico. Reported in Nature, the structure dates back to between 1000 and 800 B.C.E., before direct archaeological records of Maya writing and calendar systems. At the big complex’s very center, Inomata found the raised outlines of the pyramid-and-platform “E-group” layout thought to be a solar marker.

In a 2021 study in Nature Human Behaviour, Inomata used lidar to identify 478 smaller rectangular complexes of similar age scattered across Veracruz and Tabasco; many have similar orientations linked to sunrises on specific dates. In unpublished work with Šprajc and archaeoastronomer Anthony Aveni of Colgate University, Inomata is now reanalyzing the lidar maps to see what sunrises people at those spaces might have looked to, perhaps dates separated by 20-day multiples from the solar zenith passage, when the Sun passes directly overhead.

For later periods of Maya history, scholars seeking astronomical evidence rely more on inscriptions. Long after the Tabasco platform was erected, during a monument-building florescence spanning most of the first millennium C.E. called the Classic Period, generations of Maya lavished attention on calculating the dates of new and full Moons, sorting out the challenging arithmetic of the lunar cycle’s ungainly 29.53 days. At Copán in modern-day Honduras and surrounding cities, early 20th century archaeologists found engravings that record one “formula” for tracking the Moon that is only off by about 30 seconds per month from the value measured today; at Palenque, in southern Mexico, another version of the same formula is even more accurate.

Some recent discoveries about this time period focus on the astronomers themselves. In 2012, archaeologists described a ninth century wall mural in Xultún, Guatemala, in which a group of uniformed scholars meets with the city’s ruler. On nearby walls and over the mural itself, scholars scribbled the same kind of lunar calculations as in Palenque; one even appears to have signed their name underneath a block of arithmetic. A skeleton of a man wearing the uniform depicted in the mural was later buried under the floor of this apparent Moon-tracking workshop; a woman with bookmaking tools was also buried there.

Clues like the Xultún mural point to a network of scholars serving in Classic Period royal courts, says David Stuart, an epigrapher at the University of Texas, Austin, involved with the Xultún excavations. These specialists tracked celestial events and ritual calendars, communicating across cities and generating what must have been reams of now-vanished paper calculations. “The records we see imply the existence of libraries of records of astronomical patterns,” Stuart says, which rulers likely used to pick out fortuitous future dates.

On a deeper level, modern scholars argue that Classic Period rulers used their astrotheologians to project legitimacy. These rulers presented themselves as cosmic actors, even performing occasional rituals thought to imbue time with fresh momentum that would keep it cycling smoothly. Their dynastic histories, inscribed in stone, appear to include mythic figures and celestial bodies as forerunners and peers. Narratives of the lives of kings, for example, might harken back to the birth of a deity on the same date multiple cycles ago in the distant past. Many stories also open with descriptions of the exact phase of the Moon.

“What we’re doing now,” Stuart says, “is realizing that Maya history and Maya astronomy are the same thing.”

The four surviving codices—housed in Dresden, Madrid, Paris, and New York City—offer a glimpse of a still-later period of Maya civilization, between the Xultún workshop and the last centuries before Spanish conquest. These books were likely painted around the 1400s in Yucatán. But researchers think they contain much older records charting exactly how the Sun, Moon, and planets had appeared in the sky centuries before, from the eighth through the 10th centuries, according to Long Count dates in the Venus table and a table of solar eclipses.

After the Maya script was deciphered in the 1980s and ’90s, scholars began to probe the Venus table’s larger cultural purpose. Epigrapher Gabrielle Vail at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and Tulane University archaeologist Christine Hernández argued in 2013, for example, that the table recounts battles between Venus and the Sun, in a fusion of creation stories from the Maya and what is now central Mexico.

The table traces how Venus oscillates through its morning star-evening star routine almost exactly five times in 8 years, alongside illustrations that depict meetings between Venus in deity form and other godlike figures. Armed with this table, Vail says, a forerunner of today’s daykeepers could anticipate on what dates in the 260-day calendar such appearances might fall, and what omens they might hold.

Even the “almost” in Venus’s schedule was considered: An additional set of correction factors, provided on another page in the Dresden Codex, helps correct for how the cycle slips by a few days per century.

In a book published in March, Gerardo Aldana, a Maya scholar at the University of California, Santa Barbara, builds a case that the astronomer who devised the “correction” for the Venus predictions was a woman working around 900 C.E. He points to a figure depicted in a carving on a structure interpreted as a Venus observatory at Chichén Itzá, who wears a long skirt and a feathered serpent headdress—iconography imported from central Mexico and associated with Venus that took over in that city around that time. In another mural, a similarly dressed figure with breasts walks in a massive procession rich with feathered serpent ideology.

After the arrival of the Spanish in the early 16th century, colonizers destroyed countless codices as well as the Maya glyph system, and the long-term, quantitative sky tracking it enabled. Yet the Maya and their culture persist, with some 7 million people still speaking one or more of 30 Mayan-descended languages.

Their astronomical knowledge lingers, too, especially folklore and stories with agricultural or ecological import that have been assembled over lifetimes of systematic observation. When anthropologists visited Maya communities in the 20th century, for example, they found the 260-day calendar and elements of the solar calendar still cycling, and experts who could divine the time of night by watching the stars spin overhead. “Everybody just assumes that the knowledge has been erased, that nobody is looking at the sky,” says Jarita Holbrook, an academic at the University of Edinburgh who has studied Indigenous star knowledge in Africa, the Pacific, and Mesoamerica. “They’re wrong.”

A few days after the fire ceremony in Guatemala, at the other end of the Maya world in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, Maya elder María Ávila Vera, 84, shuffles with a cane along a path through Uxmal, an ancient city turned tourist magnet. With city lights far away, the late evening sky has deepened to an inky black. Looking up at the Greek constellation Orion, she starts to tell a story she learned in childhood about three stars in a line, symbolizing a traditional planting of corn, beans, and squash.

Unlike more detached Western approaches to studying natural phenomena, many Maya and their collaborators believe that knowledge is intricately linked to places and relationships. In this view, one of the best ways to understand past astronomers is to visit the places where they scanned the skies.

At Uxmal, Isabel Hawkins walks by Ávila Vera’s side, proffering a steady arm. Hawkins, a former astrophysicist, became fascinated with Maya culture after she began working in science education. She befriended local archaeologists, Indigenous knowledge holders like the Zunil daykeepers, Mesoamerican academics—and Ávila Vera, whom she met at an astronomy presentation to a Yucatec community in the San Francisco Bay Area.

In November 2019, this loose network gathered for a trip through Guatemala and Honduras to collaborate under a new set of methods called cultural astronomy, which emphasizes reciprocal relationships with living Indigenous sources in addition to archaeological ruins and ancient texts.

“Instead of feeling that we were behind what’s going on in other areas of the world, we felt that we were contributing to a new concept,” say Tomás Barrientos, an archaeologist who hosted part of the meeting at the University of the Valley of Guatemala.

A central task for cultural astronomers is simply to save living star lore and oral traditions that stretch back into deep time. This often involves assembling puzzle pieces. After meeting Hawkins, daykeeper Tepeu Poz Salanic began to search for surviving star stories in the Guatemalan highlands. He often visits nearby towns to play in a revived version of the ancient Maya ball game and at each stop, asks whether locals know about the stars.

One representation of ancient Maya star stories is preserved in the Paris Codex. Among the constellations it mentions are a deer and a scorpion, but the illustrations in the codex don’t come with patterns of dots to match with stars.

Locals in the town of Santa Lucía Utatlán told Tepeu Poz Salanic there was a deer in the night sky but didn’t recall where. But he knew that in the Guatemalan highlands today, the stars in what the Greeks called the constellation Scorpio are also thought of as a scorpion. (No one knows whether stories from two continents converged, or they got muddled together after colonization.) The scorpion’s K’iche’ name is pa raqan kej, “under the deer’s leg,” Poz Salanic reported in 2021 in the Research Notes of the American Astronomical Society. He thinks the deer constellation from the Paris Codex may be above the scorpion’s tail, in the constellation Western astronomers call Sagittarius.

For her part, Ávila Vera remembers practical uses of stargazing. Her godfather once brought her to a corn field before dawn and pointed to a bundle of stars that were soon washed away in the light of the rising Sun. Those stars were the Pleiades—in Yucatec, tsab, or the rattle of the snake—and he told her that the cluster’s predawn appearances began as the harvest approached. If the stars in the cluster looked distinct instead of blurry, it meant a clear atmosphere, sunny skies, and a good crop. (Similar practices persist in Indigenous communities in the Andes; in 2000, a team of scientists argued in Nature that a blurry view of the early dawn Pleiades can reliably tip off villagers to expect El Niño conditions and less rain months later.)

At 4:30 A.M. in Uxmal, the stars are shining through a thin mist, the Moon is a few days removed from full, and place, nature, and scholarship collide. Hawkins and archaeologist Héctor Cauich of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History mount steep steps to a massive complex called the Governor’s Palace. Bats flutter past their heads, returning to roost in the structure. Reaching the ancient building’s main door, the visitors turn and look east: Venus hangs in the sky straight ahead over an expanse of jungle, flanked closely by Mars and Saturn.

This vantage was created around 950 C.E. when a new ruler in Uxmal known to archaeologists as Lord Chac built up this complex. It’s a long, raised structure that is blanketed with groups of five sculptures of Chac, a Maya rain deity with a curling, trunklike nose. The façade also bears more than 350 glyphs signifying “Venus” or “star,” including under each of Chac’s eyes. More Chac sculptures, this time with the number “8” etched above their eyes, adorn the building’s corners; in 2018, Uxmal’s director, archaeologist José Huchim Herrera of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History, excavated the last two of these, confirming they share the same iconography.

Given that it takes Venus 8 years to go through five cycles, this structure practically screams its affiliation with the planet. Uxmal as a whole has been studied for decades and attracts hundreds of thousands of visitors. And yet archaeoastronomers and living Maya are still working to parse this building’s meaning. For example, on the day the planet hits the southernmost point in the sky it will ever reach, anyone standing before dawn in the main door of the Governor’s Palace and looking east would see a distant pyramid almost exactly in line with Venus. Aveni thinks the structures were positioned to create this sightline.

But Huchim Herrera is partial to another hypothesis: that the viewer is instead meant to stand on a pyramid and look west toward the building as Venus, in its guise as the evening star, rises over the Venus-spangled structure; then the key date would be when Venus hits its northernmost point. In 1990, Šprajc and Huchim Herrera, seeking the not-yet-discovered pyramid, followed the line from the Governor’s Palace main door straight into the jungle, slashing out a path with machetes. After a long morning, they found a vast, unmapped mound known to their local guide as Cehtzuc, which is still unexcavated.

If you stood on that mound, Venus’s northernmost appearance would pass directly over the Governor’s Palace and would occur in early May, when the rainy period starts in Yucatán. “The strongest motivation for any of these things is venerating water,” Huchim Herrera says.

For Ávila Vera, meanwhile, Uxmal stirs deep memories. On her last day visiting the site, she recounted a vivid recollection from girlhood: sitting by the train tracks under the shade of a tree, listening to stories about stars and ancient cities told by her grandmother, a midwife in a small Yucatec Maya town in the 1940s.

Ancient sites like Uxmal, her grandmother had said, were not places they were worthy to visit. They were sacred, ancestral homes to caretaker entities who would need to grant permission. But much later in life, Ávila Vera balanced that warning with the desire to see a place at the heart of her grandmother’s stories. She went in to Uxmal with Hawkins.

Now, she has long since crossed another threshold, going from receiving oral tradition to passing it forward. What her grandmother emphasized most by the train tracks, Ávila Vera says, first in Spanish and then in Yucatec, was the need to keep passing knowledge down to her own children.

“Le betik ka’abet a pak’ le nek’ tu ts’u a puksik’al,” her grandmother told her. “You have to plant the seed in your heart that will set the foundation.”

You may view this story in its original format at Science.