Started Out as a Fish. How Did It End Up Like This?

This story, which drew attention across social media for its catchy headline and meme-worthy subject, was one of four articles that led Sabrina Imbler to win CASW’s Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award for young science journalists in 2022. Imbler wrote the story as a reporting fellow at The New York Times and is now a writer on the creature beat at Defector.

It may not be the worst of times, but it is certainly not the best of times. The pandemic has no end in sight. The world is warming, the seas are rising and polar bears are barreling toward extinction. Also: taxes, the 9-to-5 workweek, the renewed threat of nuclear war.

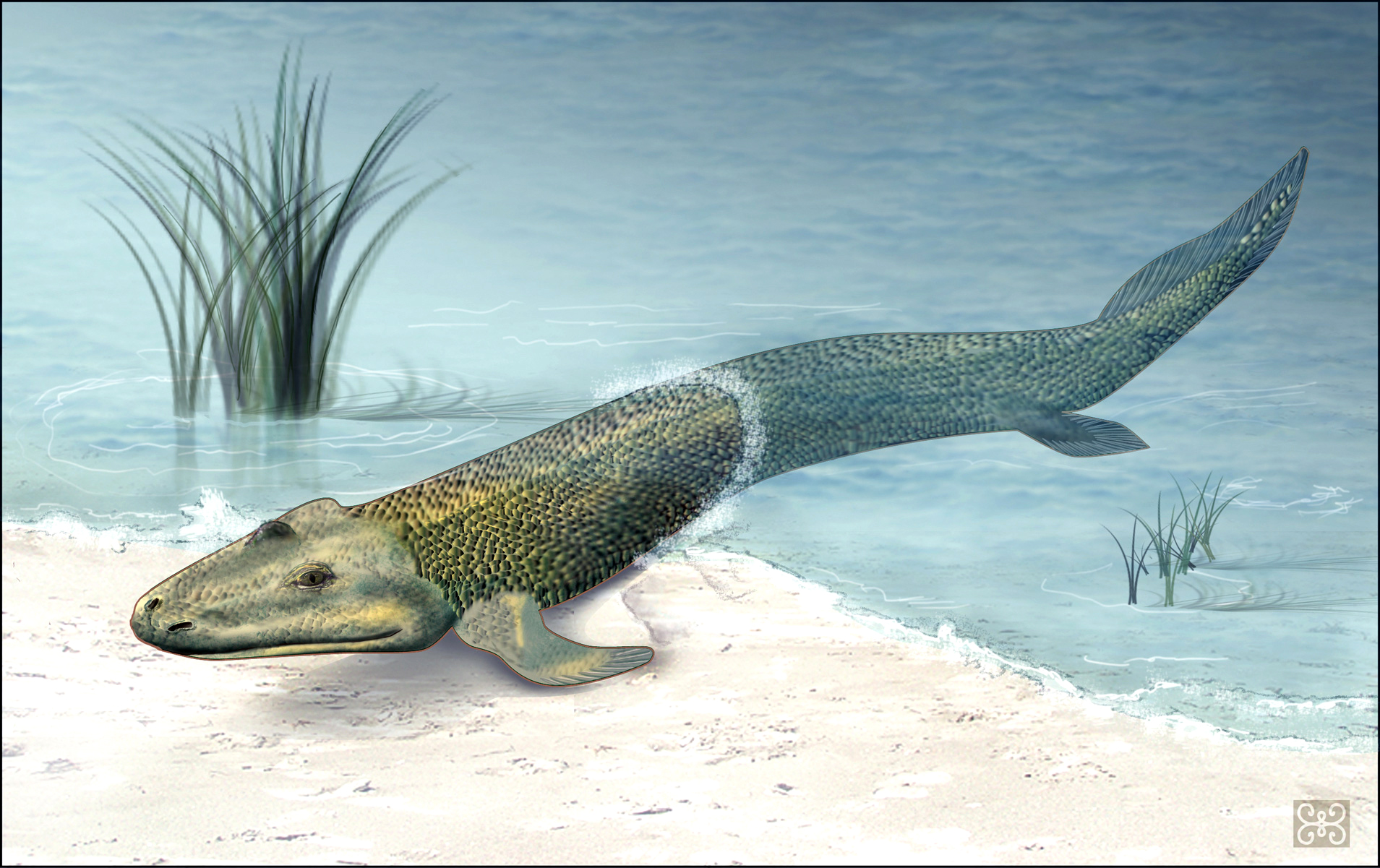

As people looked for someone to blame besides themselves and all of humanity, a culprit emerged in the form of a fish, specifically the 375-million-year-old Tiktaalik (pronounced tic-TAH-lick). Our modern woes would never have existed if our ancestors had never left the water, the reasoning went. Tiktaalik’s four whispers of feet made the fish an easy target.

In 2006, the artist Zina Deretsky made a scientific illustration of Tiktaalik for the National Science Foundation. More recently her depiction of Tiktaalik as a pensive-looking fish poised to leave the water has become the foundation for a flood of memes.

In one, the fish is met with medieval polearms and premonitions: “If you see a Horrid Beast evolving, PUSH IT BACK IN.” The memes yearn to thwack Tiktaalik with a rolled-up newspaper or poke it with a stick — anything to shoo it back into the water and avoid our having to go to work and pay rent.

When Ms. Deretsky first saw one of the memes riffing on her Tiktaalik illustration, she felt she could commiserate. “Our world is a little bit difficult right now,” she said.

Scientists may never know exactly why fish like Tiktaalik and early tetrapods — vertebrates with four limbs — moved onto land, said Alice Clement, an evolutionary biologist and paleontologist at Flinders University in South Australia. “Was it to seek out more food, escape predators in the water, find a safe haven for their developing young?” Dr. Clement asked.

Regardless, their legacy is enormous. The group of fish that moved onto land gave rise to almost half of all vertebrates today, including all amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals and us. And although we probably cannot trace our family tree directly back to Tiktaalik, “an animal very much like Tiktaalik was a direct ancestor of humans,” said Julia Molnar, an evolutionary biomechanist at the New York Institute of Technology.

If Tiktaalik is our ancestor, then perhaps our holding it accountable for the chaos it sowed is an expression of love.

‘The flop era’

Tiktaalik first became known to humans in 2004, after skulls and other bones of at least 10 specimens turned up in ancient stream beds in the Nunavut Territory of the Arctic. The discoverers, a team of paleontologists including Neil Shubin of the University of Chicago, Ted Daeschler of Drexel University’s Academy of Natural Sciences, and Farish Jenkins of Harvard University, described their findings in two Nature papers in 2006.

A local council of elders known as the Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit Katimajiit were consulted, and they gave Tiktaalik its name, which translates to a large freshwater fish that lives in the shallows, in Inuktitut. The fossils have since been returned to Canada.

Scientists had been searching for a fossil like Tiktaalik, a creature on the cusp of limbs, for decades. And where other fossils required a bit of explanation, Tiktaalik’s obvious anatomy — a fish with (almost) feet — made it the perfect icon of evolution, situated squarely between water and land.

Even then, the fossil fish struck a popular nerve, arriving on the heels of the case of a trial in Pennsylvania that ruled against teaching creationism as an alternative to evolution in high school biology. To Dr. Shubin, society’s collective desire to throw Tiktaalik back into the water is a bit of a relief: You would want to chuck the fish only if you believed in evolution, “which to me is a beautiful thing,” he said.

When Ms. Deretsky illustrated Tiktaalik, she portrayed it with its derrière submerged in water, as the fossil’s back half was a mystery at the time. But in the years since, scientists have amassed more than 20 specimens and seen more of its anatomy, including its pelvis, hind fin and the joints of its skull.

In particular, computed tomography scans taken by Justin Lemberg, a researcher in Dr. Shubin’s lab, have allowed scientists to peer inside rock to see the bones within. The scans spawned 3-D models of Tiktaalik’s unseen parts. Some scans revealed that Tiktaalik had unexpectedly massive hips (more like Thicctaalik) and a surprisingly big pelvic fin. The fish, instead of dragging itself with only its fore-fins, like a wheelbarrow, appeared to use all four fins to get around, like a jeep.

Other scans revealed the delicate bones of its pectoral fin. Unlike the symmetrical rays of fish fins, Tiktaalik’s fin bones were noticeably asymmetrical, which allowed the joints to bend in one direction. “We think that was because these animals were interacting with the ground,” said Thomas Stewart, an incoming evolutionary and developmental biologist at Penn State University.

Tiktaalik’s fins hold special allure for researchers investigating the genetic underpinnings of our own hands. Tetsuya Nakamura, an evolutionary developmental biologist at Rutgers University who hopes to genetically manipulate a zebrafish into growing fingers, hung illustrations of Tiktaalik’s fin in his lab like a beacon: “The ideal image we want to create in our lab,” Dr. Nakamura said.

Tiktaalik’s existence was ideal in other ways. The fish trundled around in the Late Devonian, an enviously halcyon version of Earth in which the climate was pleasant and mild and the seas were full of fish. Tiktaalik may have spent its days cruising around stream banks and swamps teeming with plants, Dr. Daeschler said.

That era on Earth was a goofy time to be a vertebrate, according to Ben Otoo, a graduate student studying early tetrapods at the University of Chicago. The vertebrates that did venture on land were still getting their land legs. “It’s a lot of galumphing, wriggling, slithering, huffing, flopping,” they said. “It’s literally the flop era.”

Although the Late Devonian was a dangerous time to be prey, it was also a place of mental peace — a time before self-awareness and embarrassment. “Everyone is, like, only barely conscious of the idea that they’re alive,” Mr. Otoo said. “It’s great, just vibes.”

And Tiktaalik’s flat head, with two eyes resting on top like blueberries on a pancake, made it perfectly suited for gazing above the water. “It looks like a muppet,” said Yara Haridy, an incoming researcher at the University of Chicago. “It’s very muppety.”

Other land-curious fish or early tetrapods were no less ridiculous-looking. Before Tiktaalik, flat-skulled Panderichthys swam in the shallows. Later, Acanthostega boasted a recognizable but underwhelming suite of limbs. And Elpistostege, a fish quite similar to Tiktaalik, also blurred the line between fin and hand.

So if modern humans want to blame Tiktaalik for our woes, it seems only fair that we blame all the other nascent land-dwellers — those known and those yet to be discovered — for ushering in self-awareness and W-2 forms.

The fish that launched 1,000 memes

All the known fossilized Tiktaaliks represent adult fish, so researchers hope to discover other earlier stages that could illuminate its life history, such as whether it undergoes metamorphosis.

“It would be really fun to find a bunch of babies,” said Dr. Daeschler, who will scour the Canadian Arctic again this summer. He noted that true babies would probably not ossify into fossils, as their bones are too small. But a juvenile Tiktaalik, about as long as a burpless cucumber, might have survived. And who could blame a baby for anything?

To be fair, even the adult Tiktaalik could not have predicted any of this; it had no grand plan to colonize on land. “It’s not like, ‘Oh, because limbs are better,’” Dr. Daeschler said. “Or the animals saw things on land and thought, ‘Oh, I need to evolve.’”

It is also a stretch to say the aquatic fish walked on land at all in any meaningful way. Rather, Dr. Daeschler suggested, Tiktaalik was exploiting new ecological opportunities at the water’s edge, scooting through the shallows where limbless fish could not tread.

And would-be Tiktaalik-bashers should be aware that a mere stick may not have been enough to deter an adult. Although reconstructions of its face appear “innocent and dopey,” said Dr. Stewart of Penn State University, the fish was as large as a person. “It changes the way you think about it, from kind of a little fishy thing to a more imposing animal in the water,” Dr. Stewart said.

Art need not mirror reality to convey a truth. Tiktaalik memes do not merely offer up a scapegoat for modern malaise. They also ask us to imagine a different past, present and future. What would happen if we could rechart the course of evolutionary history?

“It’s a really powerful thought, and I don’t believe there is anything inevitable about the path that evolution has taken,” Dr. Molnar said of the memes. “If you wound back the clock, you’d wind up in a completely different place,” she added, paraphrasing the biologist Stephen Jay Gould.

So if Tiktaalik signifies regret, it also signifies radical possibility. For Mr. Otoo, the fossil conjures a utopian optimism, a reminder that Earth has had many former selves and will have many more.

“The natural world we tend to think of as being very immutable and static — you look at things and say, ‘Oh, that’s how things are,’” they said. But 300 million years ago the continents were all glued together into one. Even Earth can be reshaped with time.

And if Earth can change, so too can humans, Mr. Otoo reasons. “Through various combinations of conscious and unconscious decisions, we made the created world this way,” they said. “And we can make it differently.”

Besides, who is to say that the descendants of a Tiktaalik that never left the water would not have created its own unbearable underwater world, where polymetallic nodules are harvested by unpaid octopuses and hermit crabs must pay rent on their shells? Greed can exist below the surface, too.

Abhor the message, not the messenger, Mr. Otoo advises. “You don’t hate Tiktaalik,” they said, adding: “You hate capitalism.”

You may view this story in its original format at The New York Times.