A room, a bar and a classroom: how the coronavirus is spread through the air

This visual story, published by the Spanish-language newspaper El País, provides an overview of COVID-19 risk in indoor spaces and how different safety measures may help, based on an estimation tool developed by atmospheric chemist José Luis Jiménez. Co-authors Mariano Zafra and Javier Salas won a Kavli Award, an Ortega y Gasset award, and a Malofiej award for the story in 2021. To see the full interactive graphics, read the story in Englishor in Spanish at the El País site.

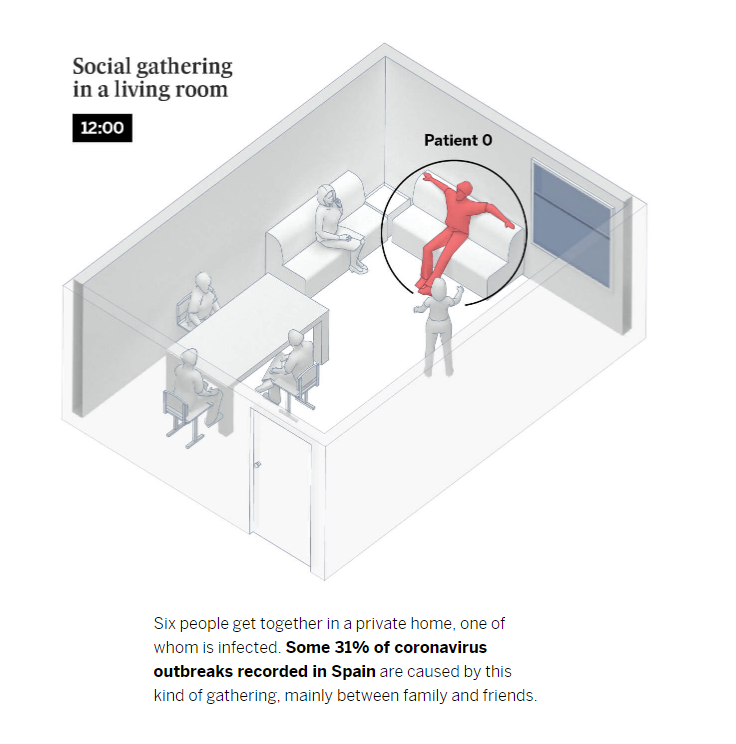

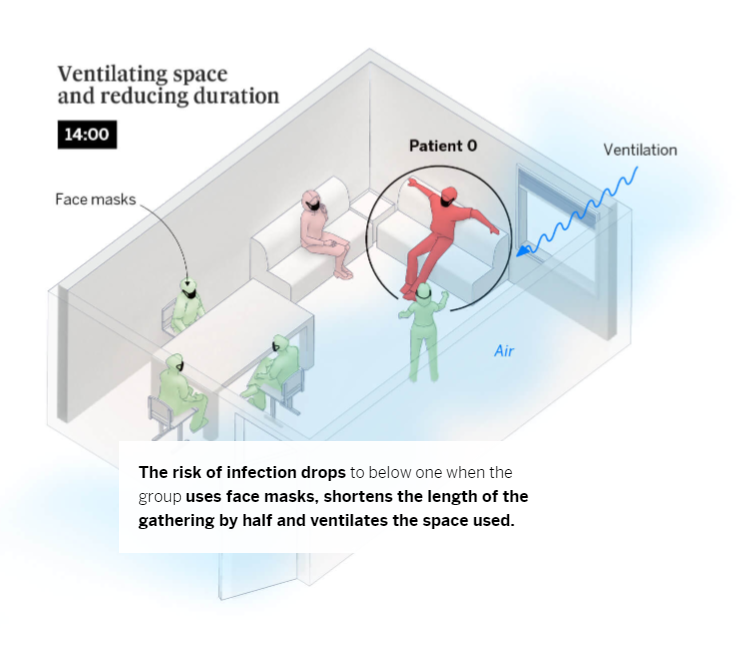

The risk of contagion is highest in indoor spaces but can be reduced by applying all available measures to combat infection via aerosols. Here is an overview of the likelihood of infection in three everyday scenarios, based on the safety measures used and the length of exposure.

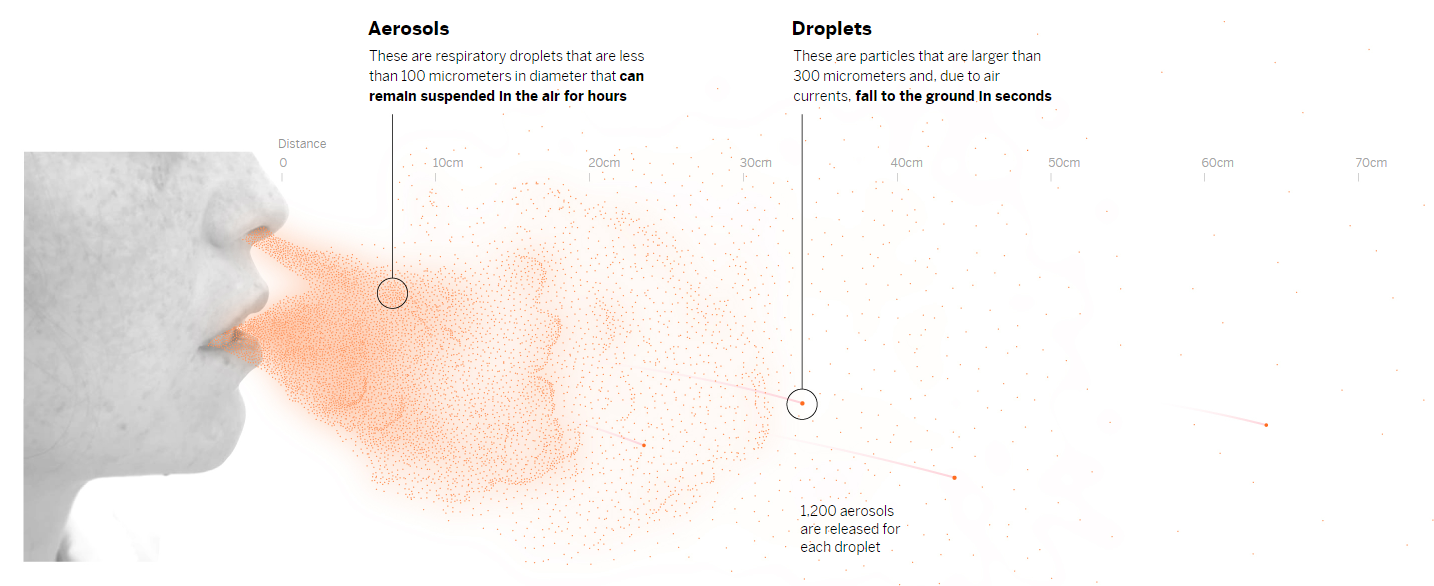

The coronavirus is spread through the air, especially in indoor spaces. While it is not as infectious as measles, scientists now openly acknowledge the role played by the transmission of aerosols – tiny contagious particles exhaled by an infected person that remain suspended in the air of an indoor environment. How does the transmission work? And, more importantly, how can we stop it?

At present, health authorities recognize three vehicles of coronavirus transmission: the small droplets from speaking or coughing, which can end up in the eyes, mouth or nose of people standing nearby; contaminated surfaces (fomites), although the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicates that this is the least likely way to catch the virus, a conclusion backed by the European Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s (ECDC) observation that not a single case of fomite-caused Covid-19 has been observed; then finally, there is transmission by aerosols – the inhalation of invisible infectious particles exhaled by an infected person that, once leaving the mouth, behave in a similar way to smoke. Without ventilation, aerosols remain suspended in the air and become increasingly dense as time passes.

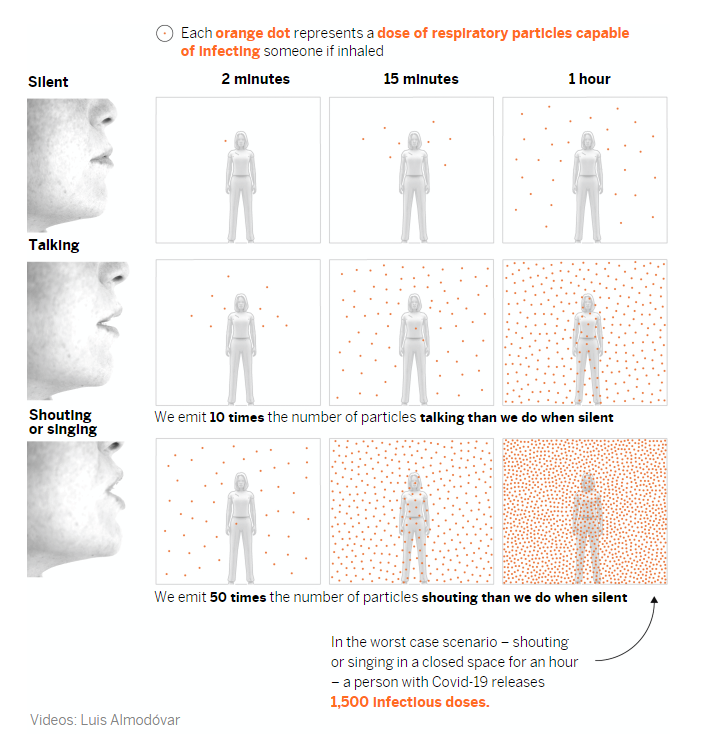

Breathing, speaking and shouting

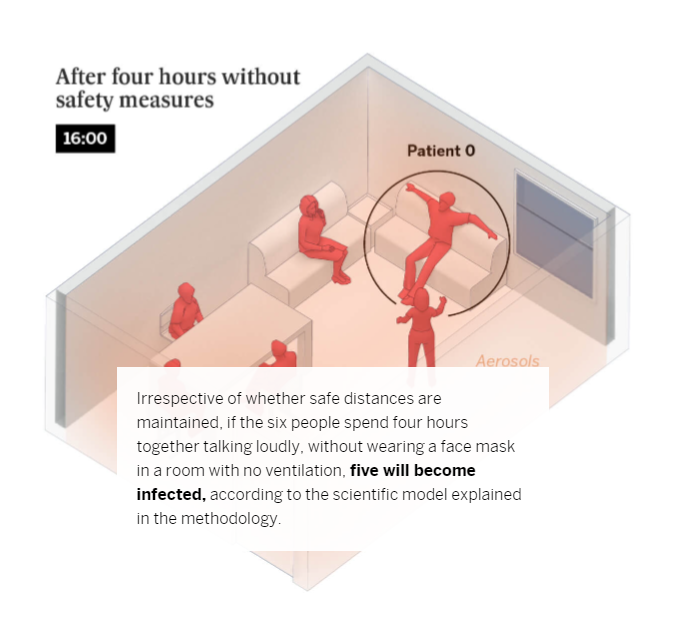

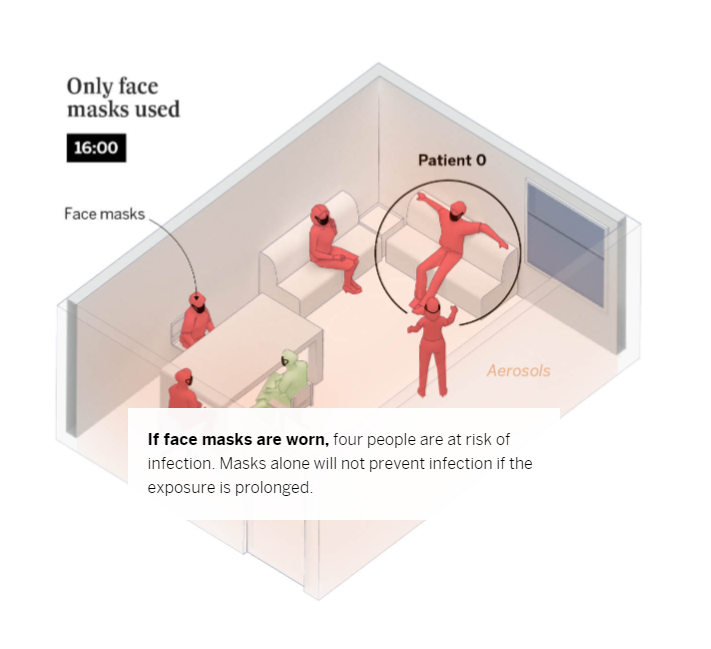

At the beginning of the pandemic, it was believed that the large droplets we expel when we cough or sneeze were the main vehicle of transmission. But we now know that shouting and singing in indoor, poorly ventilated spaces over a prolonged period of time also increases the risk of contagion. This is because speaking in a loud voice releases 50 times more virus-laden particles than when we don’t speak at all. These aerosols, if not diffused through ventilation, become increasingly concentrated, which increases the risk of infection. Scientists have shown that these particles – which we also release into the atmosphere when simply breathing and which can escape from improperly worn face masks – can infect people who spend more than a few minutes within a five-meter radius of an infected person, depending on the length of time and the nature of the interaction. In the following example, we outlined what conditions increase the risk of contagion in this situation.

In the spring, health authorities failed to focus on aerosol transmission, but recent scientific publications have forced the World Health Organization (WHO) and the CDC to acknowledge it. An article in the prestigious Science magazine found that there is “overwhelming evidence” that airborne transmission is a “major transmission route” for the coronavirus, and the CDC now notes that, “under certain conditions, they seem to have infected others who were more than six feet [two meters] away. These transmissions occurred within enclosed spaces that had inadequate ventilation. Sometimes the infected person was breathing heavily, for example, while singing or exercising.”

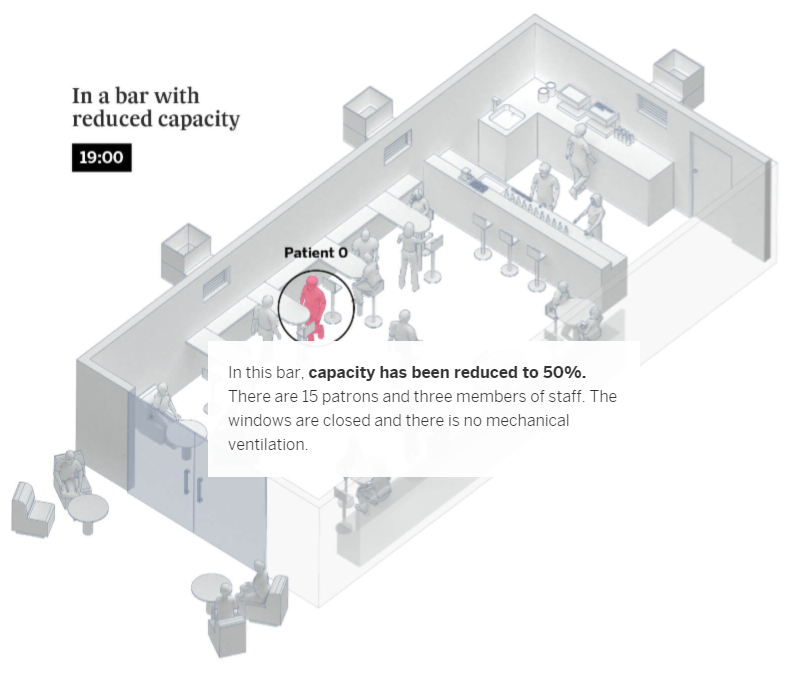

A bar or restaurant

Coronavirus outbreaks at events, and in establishments such as bars and restaurants, account for an important number of contagions in social settings. What’s more, they are the most explosive: each outbreak in a nightclub infects an average of 27 people, compared to only six during family gatherings – as explained in the first graphic. One of these superspreading outbreaks took place at a club in the Spanish southern city of Córdoba, where 73 people tested positive after a night out. Scientists have also recently analyzed an outbreak in a bar in Vietnam, where 12 patrons contracted the virus.

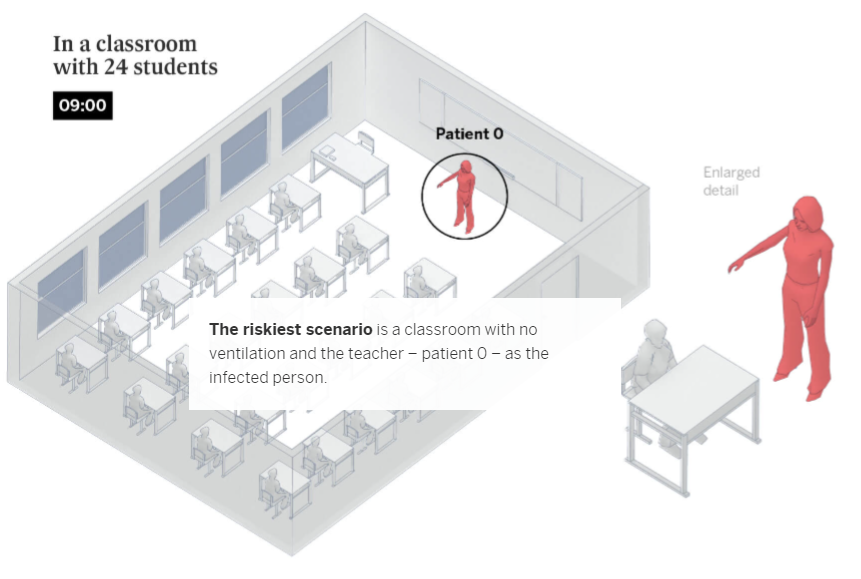

School

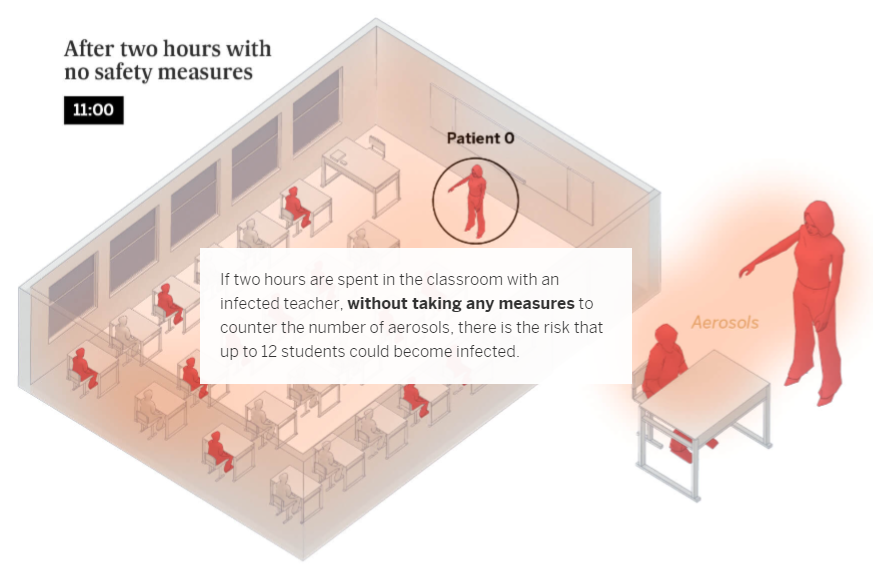

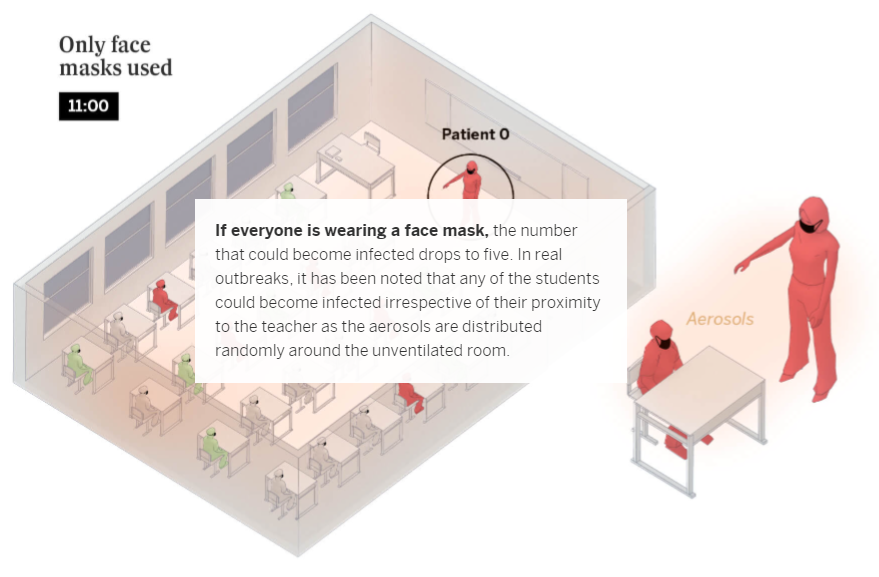

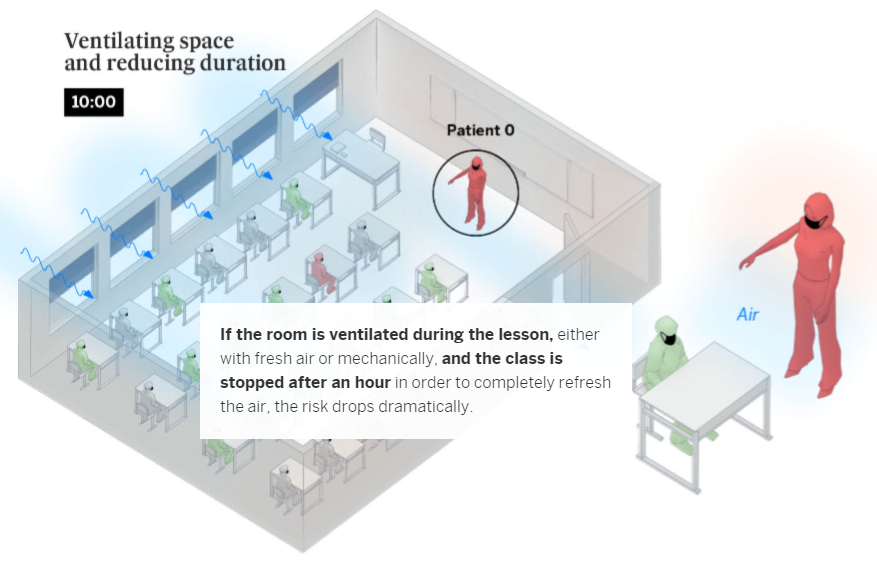

Schools only account for 6% of coronavirus outbreaks recorded by Spanish health authorities. The dynamics of transmission via aerosols in the classroom change completely depending on whether the infected person – or patient zero – is a student or a teacher. Teachers talk far more than students and raise their voices to be heard, which multiplies the expulsion of potentially contagious particles. In comparison, an infected student will only speak occasionally. According to the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) guidelines, the Spanish government has recommended that classrooms be ventilated – even though this may cause discomfort in the colder months – or for ventilation units to be used.

To calculate the likelihood of transmission between people in “at-risk” situations, we used the Covid Airborne Transmission Estimator developed by a group of scientists led by Professor José Luis Jiménez from the University of Colorado. This tool is aimed at highlighting the importance of measures that hinder aerosol transmission. The calculation is not exhaustive nor does it cover all the innumerable variables that can affect transmission, but it serves to illustrate how the risk of contagion can be lowered by changing conditions we do have control over.

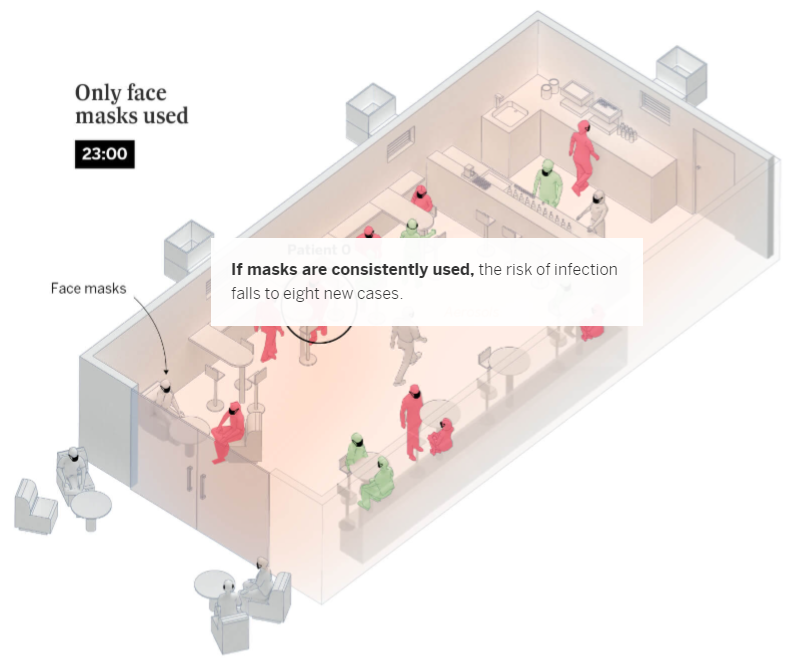

During the simulations, the subjects maintain the recommended safe distance, eliminating the risk of transmission via droplets. But they can still become infected if all possible preventive measures are not simultaneously applied: correct ventilation, shortening the encounters, reducing the number of participants and wearing face masks. The ideal scenario, whatever the context, would be outdoors, where infectious particles are rapidly diffused. If a safe distance from the infected person is not maintained, the probability of transmission is multiplied because there would also be the risk of contagion from droplets – not just aerosols. Making matters worse, even if there is ventilation, it would not be enough to diffuse the aerosols if the two people were close together.

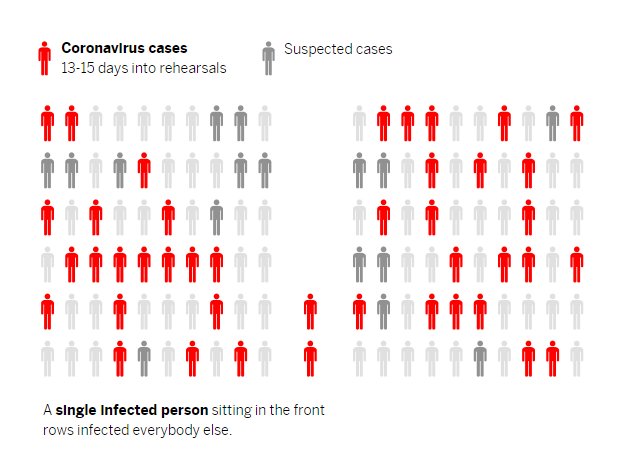

The calculations shown in the three different scenarios are based on studies of how aerosol transmission occurs, using real outbreaks that have been analyzed in detail. A very pertinent case with regard to understanding the dynamics of indoor transmission was a choir rehearsal in Washington State, in the United States, in March. Only 61 of the 120 members of the choir attended the rehearsal, and efforts were made to maintain a safe distance and hygiene measures. But unknown to them, they were in a maximum risk scenario: no masks, no ventilation, singing and sharing space over a prolonged period. Just one infected person passed the virus on to 53 people in the space of two-and-a-half hours. Some of those infected were 14 meters away, so only aerosols would explain the transmission. Two of those who caught the virus died.

After studying this outbreak carefully, scientists were able to calculate the extent to which the risk could have been mitigated if they had taken measures against airborne transmission. For example, if masks had been worn, the risk would have been halved and only around 44% of those present would have been affected as opposed to 87%. If the rehearsal had been held over a shorter period of time in a space with more ventilation, only two singers would have become infected. These super-spreading scenarios increasingly appear to be critical to the development and spread of the pandemic, meaning that having tools to prevent mass transmission at such events is key to controlling it.

Methodology: we calculated the risk of infection from Covid-19 using a tool developed by José Luis Jiménez, an atmospheric chemist at the University of Colorado and an expert in the chemistry and dynamics of air particles. Scientists around the world have reviewed this Estimator, which is based on published methods and data to estimate the importance of different measurable factors involved in an infection scenario. However, the Estimator’s accuracy is limited as it relies on numbers that are still uncertain – numbers that describe, for example, how many infectious viruses are emitted by one infected person. The Estimator assumes that people practice the two-meter social distancing rule and that no one is immune. Our calculation is based on a default value for the general population, which includes a wide range of masks (surgical and cloth), and a loud voice, which increases the amount of aerosols expelled.

Videos by Luis Almodóvar, English version by Heather Galloway.

You may view this story in its original format at El País in English and in Spanish.